Every now and then, I represent small companies in fighting citations issued by the Occupational Safety & Health Administration where OSHA jurisdiction becomes a legal defense issue. If jurisdiction is lacking, OSHA citations and penalties must be dismissed. Federal OSHA has jurisdiction over most private sector employers in 29 states (exceptions include operations at mines, quarries, and cement plants). State-run OSHA agencies handle inspections and prosecutions in the remaining 21 states, and the discussion below relates to federal OSHA definitions—the law could be different if you are under a state-based OSHA agency and statute.

For federal OSHA purposes, the Occupational Safety & Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act) delineates the scope of the agency’s authority. Section 3 of the federal OSH Act contains the language that is significant with respect to coverage of companies. It states, in relevant part: “The term ‘employer’ means a person engaged in a business affecting commerce who has employees . . . . The term ‘employee’ means an employee of an employer who is employed in a business of his employer which affects commerce.”

Granted, this has a bit of circular logic to it. But it comes down to this: Does a company have employees or not? If not, OSHA cannot cite it or fine it. A published decision sheds light on how this defense can be raised and sustained to the company’s benefit. In Secretary of Labor v. Ehle, Inc. (ALJ 2012), the court had to analyze the status of co-owners and temporary workers used by the company to carry out its activities.

THE ISSUE

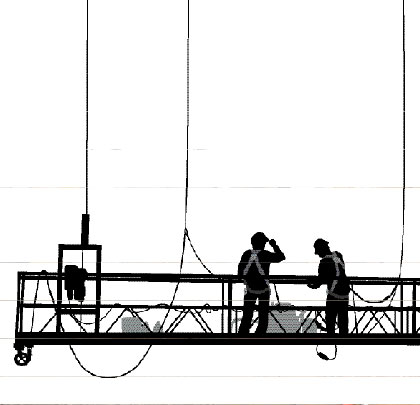

OSHA had conducted an inspection at the company’s worksite and as a result issued two serious violations, which were contested on the basis that the company was not an “employer” pursuant to the OSH Act. At the time OSHA visited, roofing was being installed on an apartment building that was under construction. The inspector observed workers on the roof without appropriate fall protection.

Ehle Inc. owned the rental apartment properties, which were being constructed using subcontractors. Once the apartments were built, a management company was used to maintain the property. The company had two co-owners (brothers named Ehle) who made all corporate decisions but did not draw a salary from the company for the work they performed on site.

During the OSHA inspection, the inspector asked who was in charge and was directed to one of the owners, who told OSHA that they had no safety and health programs. The inspector then interviewed a worker, Chuck Brandau, who said that he had not been trained on fall protection requirements, but who also provided information regarding his status as an independent contractor.

Based on the record at trial, the judge found that the company was engaged in a business affecting commerce (one prerequisite for OSHA jurisdiction), so the analysis turned to whether it had any “employees” within the meaning of the OSH Act. The company argued that neither of the Ehle brothers were employees because they were co-owners who were not drawing a salary. It further argued that the subcontractors performing the construction work were not employees, either.

The judge first looked at the subcontract worker, Brandau, who was a carpenter and operated under the business name of RC Construction. Brandeau had worked previously for the Ehle brothers on another project a few years earlier, and would have worked on the current project for about one week. He was to be paid according to the number of hours worked. At the end of the job, he would be paid using a 1099 form for tax purposes. Brandau provided his own tools, but Ehle provided the heavy equipment and materials. Brandau also told the inspector that he had refused to work on a windy day, without objection from Ehle, and that he shared decision-making responsibilities about the roofing project.

THE OUTCOME

In analyzing the definitions of employer and employee within the OSH Act, the court found that because these terms were not clearly defined, a common-law agency doctrine of “master-servant” would be applied. Quoting an earlier decision, the court found:

In determining whether a hired party is an employee under the general common law of agency, we consider the hiring party’s right to control the manner and means by which the product is accomplished. Among the other factors relevant to this inquiry are the skill required; the source of the instrumentalities and tools; the location of the work; the duration of the relationship between the parties; whether the hiring party has the right to assign additional projects to the hired party; the extent of the hired party’ discretion over when and how long to work; the method of payment; the hired party’s role in hiring and paying assistants; whether the work is part of the regular business of the hiring party; whether the hiring party is in business; the provision of employee benefits; and the tax treatment of the hired party.

In short, the court will look to the “element of control” over the hired party. Based on the facts in this case, the judge held that OSHA failed to establish that Brandau was an employee of Ehle Inc. While some factors mitigated in favor of finding an employment relationship, the weight of evidence suggested that the employer-employee relationship was lacking—especially because of the multi-year gap between projects, the limited scope of the current work, and the use of the 1099 for tax purposes.

The court also held that the Ehle brother who was on the roof at the time of inspection was not an employee but was a controlling employer and that the other brother did not exercise control over his actions in a way that would indicate an employer-employee relationship. The income received by the brothers flowed from rents for the properties, rather than from the work they performed. The court was unwilling to find that merely because an individual is a corporate officer he is automatically an employee of the company. Shareholders and corporate officers are not “ipso facto” employees; rather than focusing on titles, the judges are to focus on the work performed and the manner in which such individuals are paid. Because jurisdiction was lacking under the OSH Act, the citations were vacated.

■ ■ ■

[divider]

About the Author Adele L. Abrams, Esq., CMSP, is an attorney and safety professional who is president of the Law Office of Adele L. Abrams PC, a ten-attorney firm that represents employees in OSHA and MSHA matters nationwide. The firm also provides occupational safety and health consultation, training, and auditing services. For more information, visit www.safety-law.com.

Modern Contractor Solutions, July 2014

Did you enjoy this article?

Subscribe to the FREE Digital Edition of Modern Contractor Solutions Magazine!